David Walsh owns a cricket bat autographed by stars of the 1980s: Greg Chappell, Dennis Lillee, Viv Richards and Abdul Qadir to name a few (the bat got signed mostly at the 1983–84 Australian Tri-Series, where Australia hosted Pakistan and the West Indies). David shows his mates and they refuse to bowl at him. ‘You can’t play cricket with that!’ they cry. ‘Of course I can, it’s a fucking cricket bat,’ he replies. He’s wrong, of course, and he knows it. Not only does he know it’s a special cricket bat—an unsigned bat cannot take its place—it’s no longer really a cricket bat at all.

This is not an exhibition about cricket. But the status of David’s non-cricket bat brings certain questions into focus. Why are we drawn to certain objects and people? What makes the big names big: Porsche, Picasso or Pompidou? What is the nature of status and why is it useful? Is it just culture, or is there something deeper? Do we have certain ways of caring that our distant ancestors shared, and maybe even benefitted from? Are our choices shaped by culture, or is our culture shaped by nature’s choices?

What makes the big names big: Porsche, Picasso or Pompidou?

One possible explanation is essentialism, which is the sense that things and people have an essence, spirit or soul, that transcends their material state. Figuring out whether or not this can provide an accurate description of the world isn’t really our objective; essentialism appears to be more about perception, the way we think about things.

Why are we drawn to certain objects and people?

Are things—like cricket bats, works of art, books, and other special objects—meaningful to us as a proxy for this essence? Is that why we (people in general) love originalé, and get upset about fakery, not to mention modern art that thwarts detection of ‘the artist’s hand’? Just try feeling the same way towards a mass-produced paperback copy of the Origin of Species as you do a hand-annotated manuscript. Might we somehow touch the genius of Picasso by holding a ceramic plate created by his studio but not potted and painted by the master himself? And would you eat your tea from such a dish?

What is the nature of status and why is it useful? Do we have certain ways of caring that our distant ancestors shared, and maybe even benefitted from?

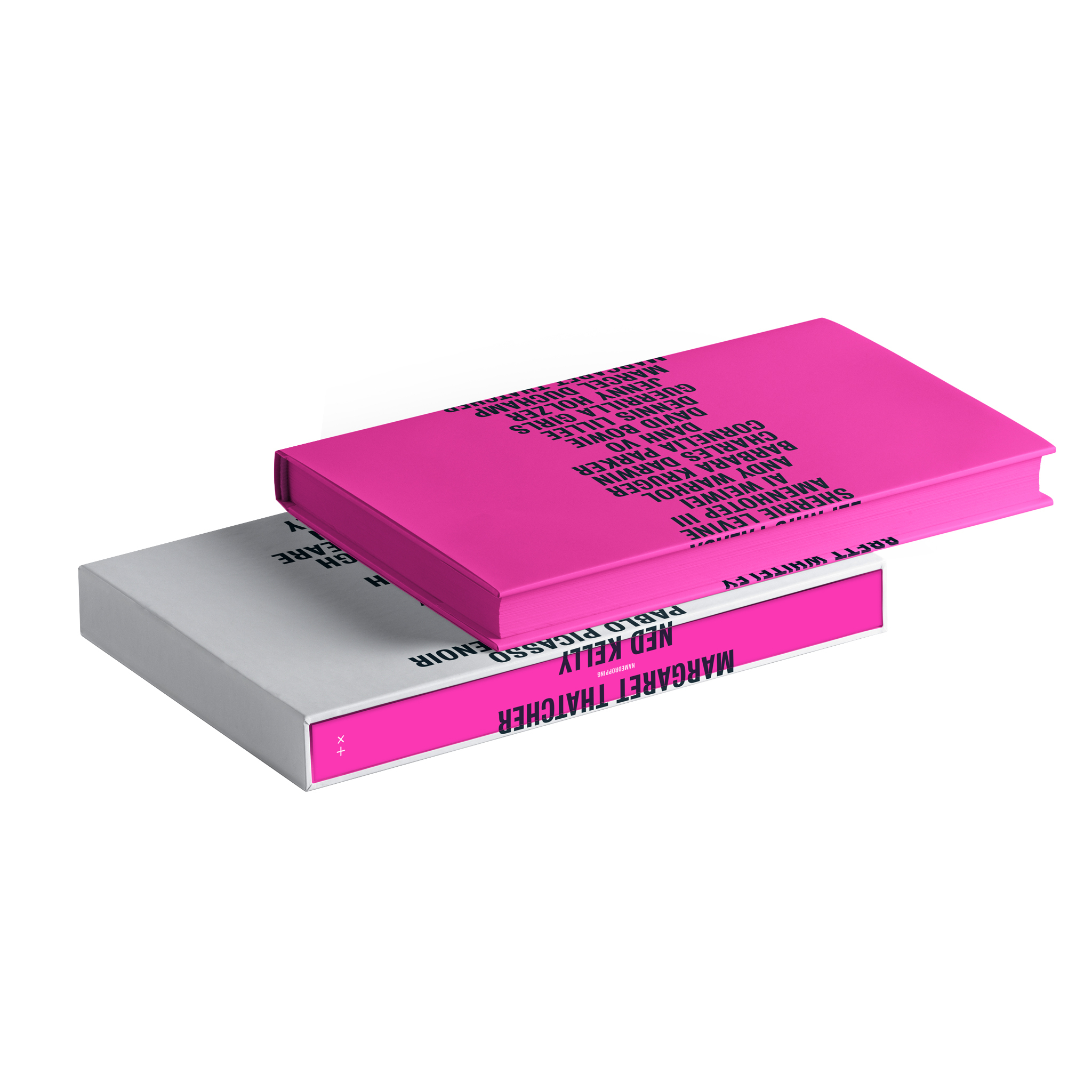

This is where status and our ferocious human pursuit of looking good in the eyes of others come into play. A fundamental component of creativity appears to be its use as a status enhancer, for attracting appropriate mates and allies—which is biologically useful and, in the grand scheme of evolutionary history, has helped you survive and to cycle your genes into future generations. This is why we believe namedropping, signalling for status by association—be it for getting sex, power, enhanced reputation or in-group identity—is probably a universal human instinct. Social position is a life and death matter for human beings. Put simply, we are not evolved to survive and thrive alone. We’re born with brains primed to think about what other people think about, to pick out carers and kin and then, as the years go by, who’s socially helpful and what’s ‘special’. Namedropping can help you influence other people’s thoughts and narrow down who takes notice. And of course, what evolved for status-seeking and happy social interaction in our ancestral environment (come back to my cave and see my etchings) can have all sorts of different outcomes in modern life (eating too much foie gras is bad for you, while shark fin soup is very bad for sharks).

Are our choices shaped by culture, or is our culture shaped by nature’s choices?

This is not the first time we’ve laid our cards on the table with a hypothesis about art not based in culture. Saying that art is useful in a deep, biological sense doesn’t mean you have to throw the cultural baby out with the bathwater. But if art were purely cultural, it would be a choice. If art were a choice made by those who make it, why are there no cultures that don’t make art? And why do all individuals explore creativity in their childhood? Culture gives us an excuse; biology gives us a motive. This is our human burden: feeling our way through the strange binding of ancient brains and modern circumstances. But it’s also, in many other ways, our blessing: an excuse to stop lying to ourselves about the base urges and better angels of our human nature. In the words of that most pre-eminent of Australian legal minds, Dennis Denuto, it’s the vibe.

That’s enough fine talk for now, which as we know, doth butter no parsnips. But let us leave you with this. All art—and all namedropping for that matter—is communication: sometimes broadcast for maximum but indiscriminate everyone-knows-Picasso effect; but often narrowcast and targeted. Because whether you know it or not, you don’t need everyone to like your particular brand of bullshit.

Namedropping